I have been haunted for two and a half years by this “Fr. Z” blog post that shows how American Catholics fasted for lent in the 19th century:

DIOCESE OF NEWARK. (1873) REGULATIONS FOR LENT:

Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent, will fall on the twenty-sixth day of February.

1. Every day during Lent except Sunday, is a day of fast on one meal, which should no be taken before mid-day, with the allowance of a moderate collation in the evening.

2. The precept of fasting implies also that of abstinence from the use of flesh meat, but by dispensation, the use of flesh meat is allowed in this Diocese at every meal on Sunday, and at the principal meal on Mondays, Tuesdays and Thursdays, of Lent except Holy Thursday. [But not Wednesday and Friday and Saturday]

3. There is no prohibition to use eggs, butter or cheese, provided the rules of quantity prescribed by the fast be complied with. Fish is not to be used at the same meals at which flesh meat is allowed.

Butter, or if necessary lard, may be used in dressing of fish or vegetables.

4. All persons over seven years of age are bound to abstain from the use of flesh meat, and all over twenty-one to fast according to the above regulations unless there be a legitimate cause of exemption. The Church excuses from the obligations of fasting, but not from that of abstinence from flesh meat, except in special cases of sickness or the like, the following classes of persons: 1st, the infirm; 2nd, those whose duties are of an exhausting or laborious character; 3rd, women in pregnancy, or nursing infants; 4th, those who are enfeebled by old age. In case of doubt in regard to any of the above exemptions, recourse must be had to one’s spiritual director, or physician.

All alike, should enter into the spirit of this holy season, which is, in a special manner, a time of prayer, and sorrow for sin, of almsgiving, and mortification.

The faithful are reminded that by a special privilege granted d by the Holy see to the faithful of this Diocese, a Plenary Indulgence may be gained on the usual conditions, on St. Patrick’s Day or any day, within the Octave.

By order of the Very Reverend Administrator,

GEORGRE H. DOANE. Secretary.

Bishop’s House, Newark, Feb. 6., A.D. 1873.

Consider the fact that the above was how most of the Catholic world fasted before 1917. Consider the fact that most of the people in Newark were working factory jobs or raising many children (that is, blue collar work.) Consider the fact that the above is pretty close to how Russian Orthodox and Byzantine Catholics today attempt to fast at least twice a year, and sometimes several times a year (e.g. Assumption Fast.) All Apostolic Christians, East and West, were expected to live a fast like the above list of rules until probably about the beginning of the 20th century.

A bit late—only a few years ago—the UK bishops, probably fearing for the Catholic identity of the flock, announced that the substitutionary penance in place of no-meat Fridays outside Lent was overturned. In other words, it’s 50 Fridays a year of no-meat in England today (unless they flip-flopped again.) It’s a nice start, but probably too late to recover the Catholic identity. But what really troubles me even more about our current practice worldwide is not the aspect of Catholic identity, but the fact that when we Christians don’t fast anymore, it actually affects our salvation: “For to set the mind on the flesh is death, but to set the mind on the Spirit is life and peace. For the mind that is set on the flesh is hostile to God, for it does not submit to God’s law; indeed, it cannot. Those who are in the flesh cannot please God.”—Romans 8:6-8. (No, St. Paul was not a Pelagian!)

In seminary, I often said stupid things like: “Before Vatican II, we had to fast for rules. Now we get to fast for love.” There’s a little truth in that, insofar as the Catholics today that love God fast. But the bigger problem with what I asserted in seminary is this: The new “rules” forget original sin! It forgets that in a family of one billion Catholics, not everyone wants to live as a St. Gerard Majella on air and prayer. While a Catholic world of rules without relationship leads to rebellion, a Catholic world of relationship without rules leads to a surrender, without content. A Catholic world that is not obliged to fast except when we are urged on via great charity in the Holy Ghost will—in 99% of Catholics—lead to minimalism and eventually nothingness. Why? Because concupiscience that remains after baptism always pulls us to lowest common denominator Catholicism. If we don’t have something hardcore (like the rules outlined above) then the flock is going to choose the path of least resistance. If you think I’m exaggerating by that word nothing, ask all your Catholic friends if they ever fast outside Lent. Ask your parish priest if he stays meat free on Fridays. When he says “No,” remind him that even the 1983 Code of Canon Law requires 50 meat-free Fridays a year (as explained here in #14.) But even that #14 rule is so small as to be nearly nothing.

This isn’t just me complaining about the past for the sake of the past. I recently explained in a podcast here (minute 12) to a group of University Students the following notion: Protestantism spread through catechesis while Catholicism spread through the ascetical life. Why did Catholicism spread through the ascetical life? In the early Church, the pagans would see children being tortured in the amphitheater while these children sang praises to God. The pagans then converted when they saw in the flesh such charity and fortitude – mere children loving God more than their own bodies. Many people wrongly believe that God simply dulled the pain nerves of martyrs. While this is true on rare occasions, most spiritual writers (including St. Thomas Aquinas) teach that dulling the pain nerves is rare. What is more common is that the level of charity in a martyr (built up through God’s grace) was simply at a higher level than the physical pain. In other words, their physical pain was real, but their love of God was even more real.

They usually got there—to that level of an invincible relationship with Jesus Christ—through bringing the spirit alive via many years of “dying” to the body. The study of this self-denial is called ascetical theology. It has nothing to do with Pelagianism and everything to do with the simple fact that the more we pour out, the more the Holy Spirit pours in.

Through the Middle Ages, one glance at a saint in the unitive way of prayer often converted a pagan who looked at a saint. How did the saints get to this spiritual marriage with God? They passed through the purgative way of prayer, then the illuminative way of prayer and finally the unitive way of prayer through great denial of their will in both matters of taste and of preference. I mentioned in the above -linked podcast that when a lapsed Catholic in 16th century Spain simply saw the radiance of the face of a St. Catherine of Siena or St. Teresa of Avila (such a cloud of grace surrounded such saints) that simple lay people (who had gone to Mass their whole lives with no fervor) would experience immediate conversions after being in the presence of these two great Saints. Does that mean it’s greater to be in the presence of St. Teresa of Avila than the Holy Eucharist? Of course not. But for some reason God has attached major consolation to being in the presence of a saint that doesn’t always come with the infinite grace poured out at Holy Mass.

The ascetical life brought the world to Christ. Franciscan missionaries who had fasted their way into the unitive stage of prayer would show up in foreign lands and everyone would see Christ shining through their faces! The pagans wanted to be Catholic without the need for apologetics. The Irish king who decided he hated St. Patrick before meeting him, one day saw the saint’s face and said how much he loved him! Yes, Catholicism spread through the ascetical life more than through catechesis and Scriptural typology (as much as I love all three of those parts of Our Faith.) This is because, in some sense, the Apostle Paul seems to imply we can’t even be in a state of grace if our body is not dead to some extent: “But if Christ is in you, although the body is dead because of sin, the Spirit is life because of righteousness. If the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, he who raised Christ Jesus from the dead will also give life to your mortal bodies through his Spirit who dwells in you.”—Romans 8:10-11

None of this is to scare my readers into fasting more or whipping yourselves. We are only bound by the 1983 Code of Canon Law. But I am saddened by it, not because I want rigorism or Jansenism, but because I feel so much closer to God when I fast… and I could use a little fire under my tail (rules) to keep me going when I get tired or depressed. In other words, I often excuse myself from fasting beyond what the current law dictates due to my own concupiscence. And I know that if I had hardcore rules (like those seen at the beginning of this blog post) I would more rapidly advance from the purgative way of prayer to the illuminative way of prayer to the unitive way of prayer. And then be in union with Christ. And then convert a lot more people.

So many Catholics today are becoming Russian Orthodox or Buddhist or Hindu (not that those religions are on the same plane by any means) because they long for an ascetical life of meditation and fasting that is central to those religions (as it was once to Catholicism.) I long for fasting norms like that again not to be more “hard core” than the next Catholic blogger but because I know that a billion Catholics fasting on 40 days with no meat, no dairy and minimal oil would nearly wipe out millions of Catholic addictions to drugs, porn, alcohol, video games, etc. Again, this is not because of Pelagianism, but because when we die our tastes in grace, it bring us into union with Christ crucified.

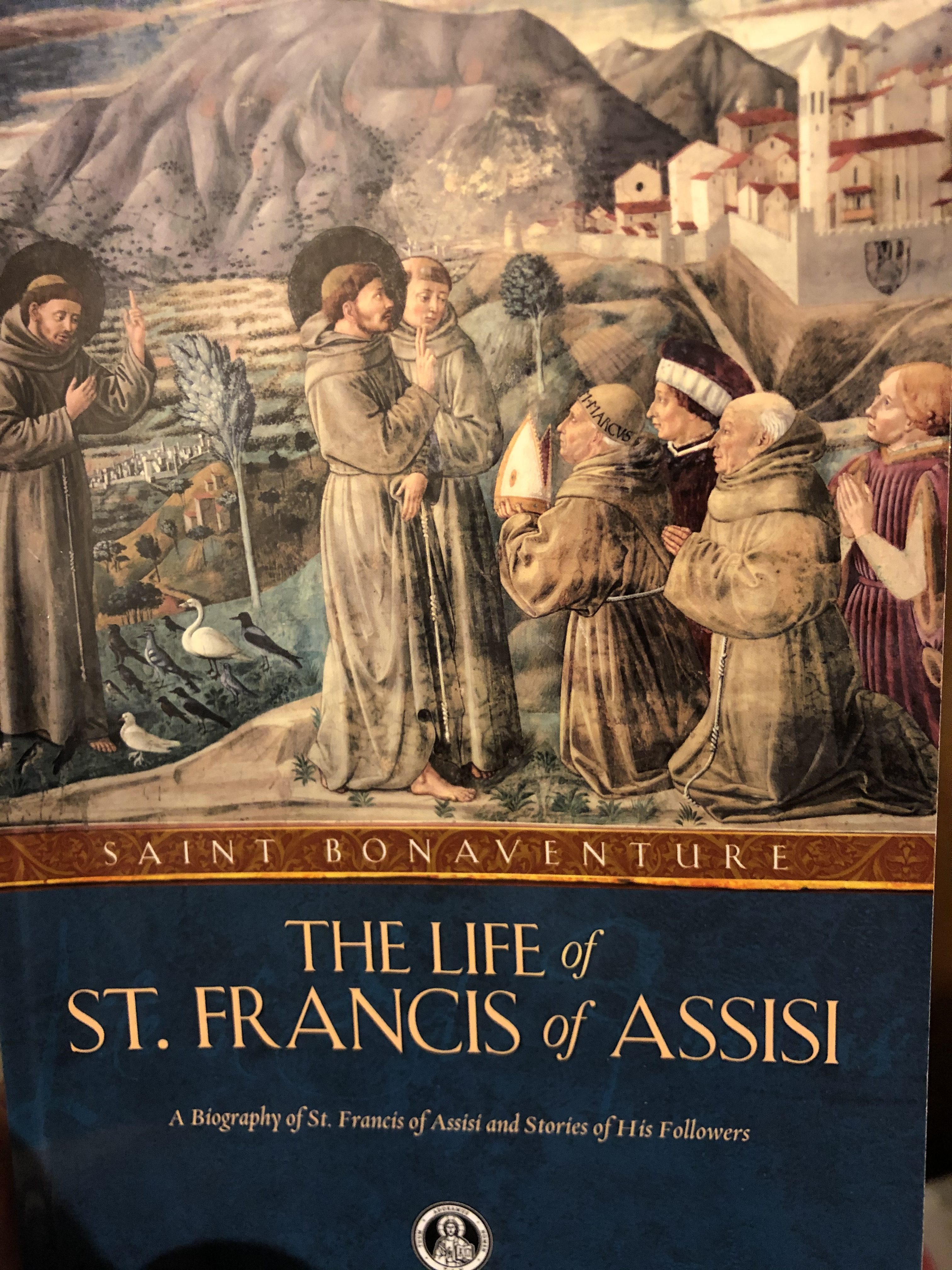

After so many decent books (and bad movies) on St. Francis of Assisi, I have finally come across the only necessary book on the life of the poor saint of Italy: The Life of St. Francis of Assisi by St. Bonaventure. As the Archbishop of Westminster wrote in 1867, “The life of a saint, written by a saint…speaks to the heart with a vital power…It has a twofold operation of the Spirit of God with it, both in the subject and in the writer.” Yes, when it comes to such a malleable saint such as Francis of Assisi, only a biography by another saint who knew him will do – St. Bonaveture, who lived with him in the 13th century left us such a treasure. Unfortunately today, St. Francis has become the single most abused saint, who, by so many post-modernist, has been made out to be a sort of hippy ecologist in their own image. But the fact is, St. Francis was able to make so many millions of people Catholic because of grace, surrender, love and…the ascetical life.

If a man as pure as St. Francis (who yes, did remain a virgin his whole life) needed to fast so much to stay pure (St. Bonaventure repeatedly says so) then how much more do we need the old school rules? And if we can’t force upon ourselves the old-school rules, then we should realize that a great deal of our own salvation (and the spread of the Catholic faith) which depends on the ascetical life, stands in the balance. Consider finally what St. Bonaventure had to say about the ascetical life of St. Francis of Assisi:

“[St. Francis of Assisi] continually discovered new ways of exercising abstinence, increasing daily in its exercise; and even when he had attained the summit of perfection, he still endeavored, as if only a beginner, to punish, by fresh macerations, the rebellion of the flesh…The bare earth was the ordinary bed of his wearied body, and he often slept sitting, leaning his head against a stone, or a block of wood…Now the holy man Francis watched most diligently over himself, becoming ever more and more rigid in his care of the purity both of the interior and exterior man, for which cause, in the beginning of his conversion, he would often plunge in winter-time into a pit of ice and snow, that he might more perfectly subdue his domestic enemy, and preserve the white garment of his purity from the fire of temptation. For he said that it was beyond comparison for a spiritual man to endure the utmost extremity of cold in his body, than the slightest spark of sinful passion in his soul.”— St. Bonaventure, chapter 5 of The Life of St. Francis of Assisi.